From Classroom to Creative

Page 4: The evolution of exercise books

I’ll never forget the day my teacher picked up a brand-new exercise book, flipped it open, and—with no warning—shoved his face into the crisp white pages. He took a deep, exaggerated breath and said, "Ahh, nothing like the smell of a fresh exercise book". Or at least that’s how I remember it; I was only 10 years old so my memory’s a little hazy. The whole class laughed, but it stuck with me. There was something about his delight in that moment that made me realise how a new notebook can make you feel. How something so simple can spark joy, creativity and inspiration all at once.

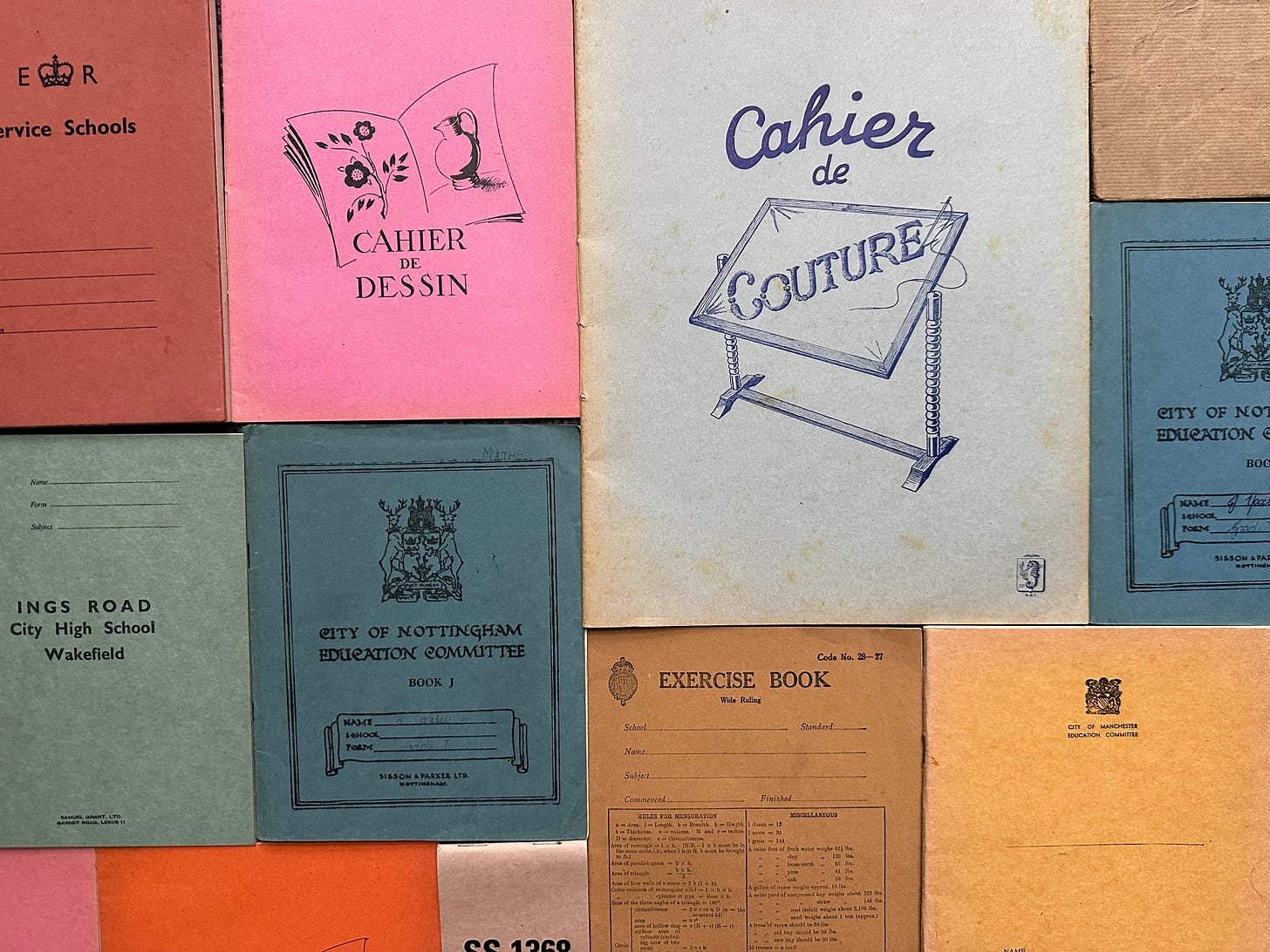

That memory stayed with me long after school. I continued using exercise books, and even started collecting vintage ones (see image above). Then I started making my own—that’s why I’m starting PREST. But the story of exercise books goes back centuries, far beyond my own school memories.

Regional variations

The terminology and format of exercise books varies across different countries and regions. In the UK, they’re called “exercise books” (or “jotters” in Scotland). In India, they’re called “khata”. In Canada, quite charmingly, they’re called “scribblers”. In the US, they’re called “composition books”. And in France, they’re known as “cahiers”.

Origin — A tool for learning

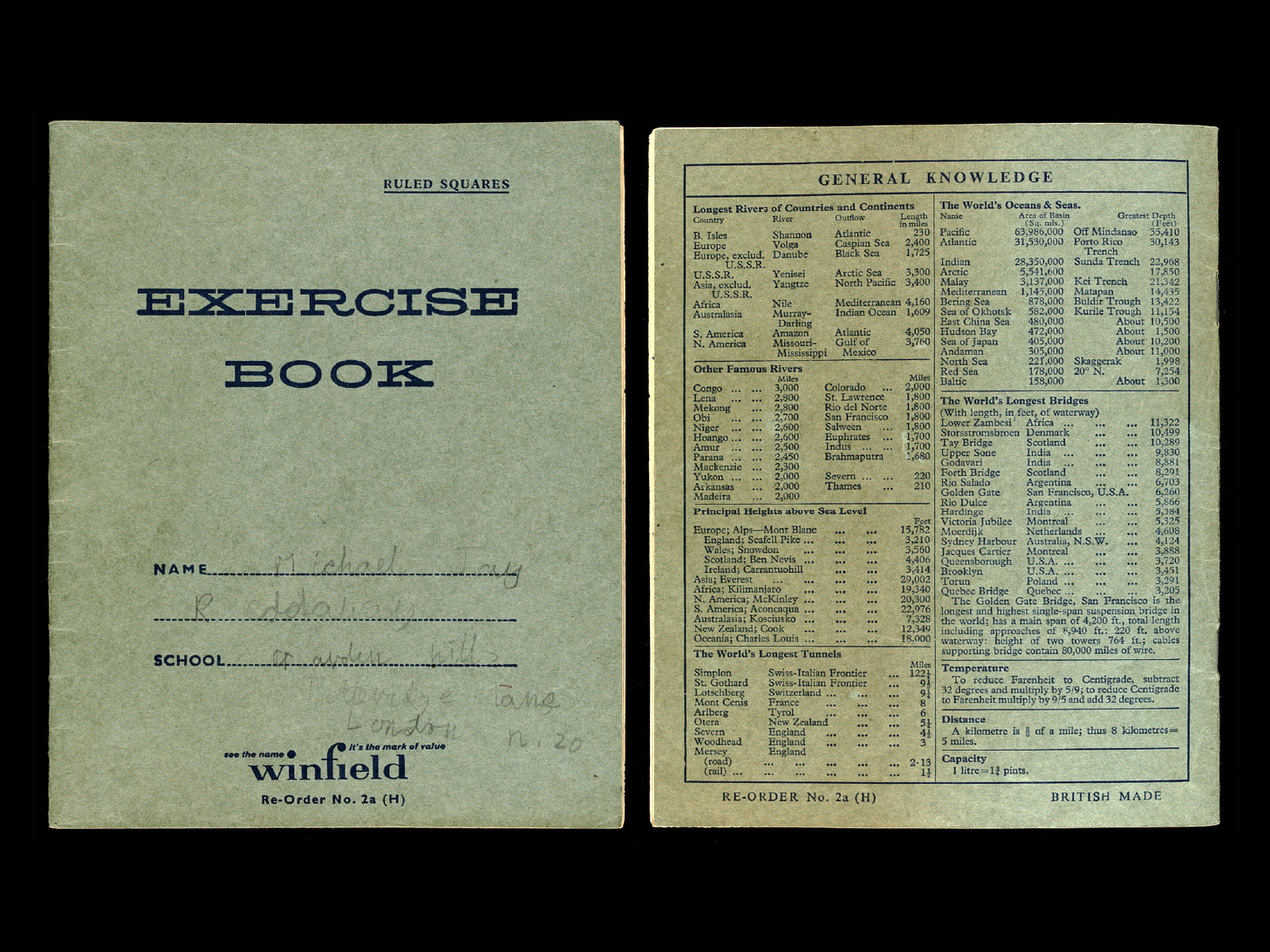

Exercise books have deep roots in education. The Renaissance sparked a revolution in how we recorded knowledge, with a rise in note-taking and the use of books for learning. Fast-forward to the 19th century and exercise books had become essential in the classroom, offering a space for students to learn and grow.

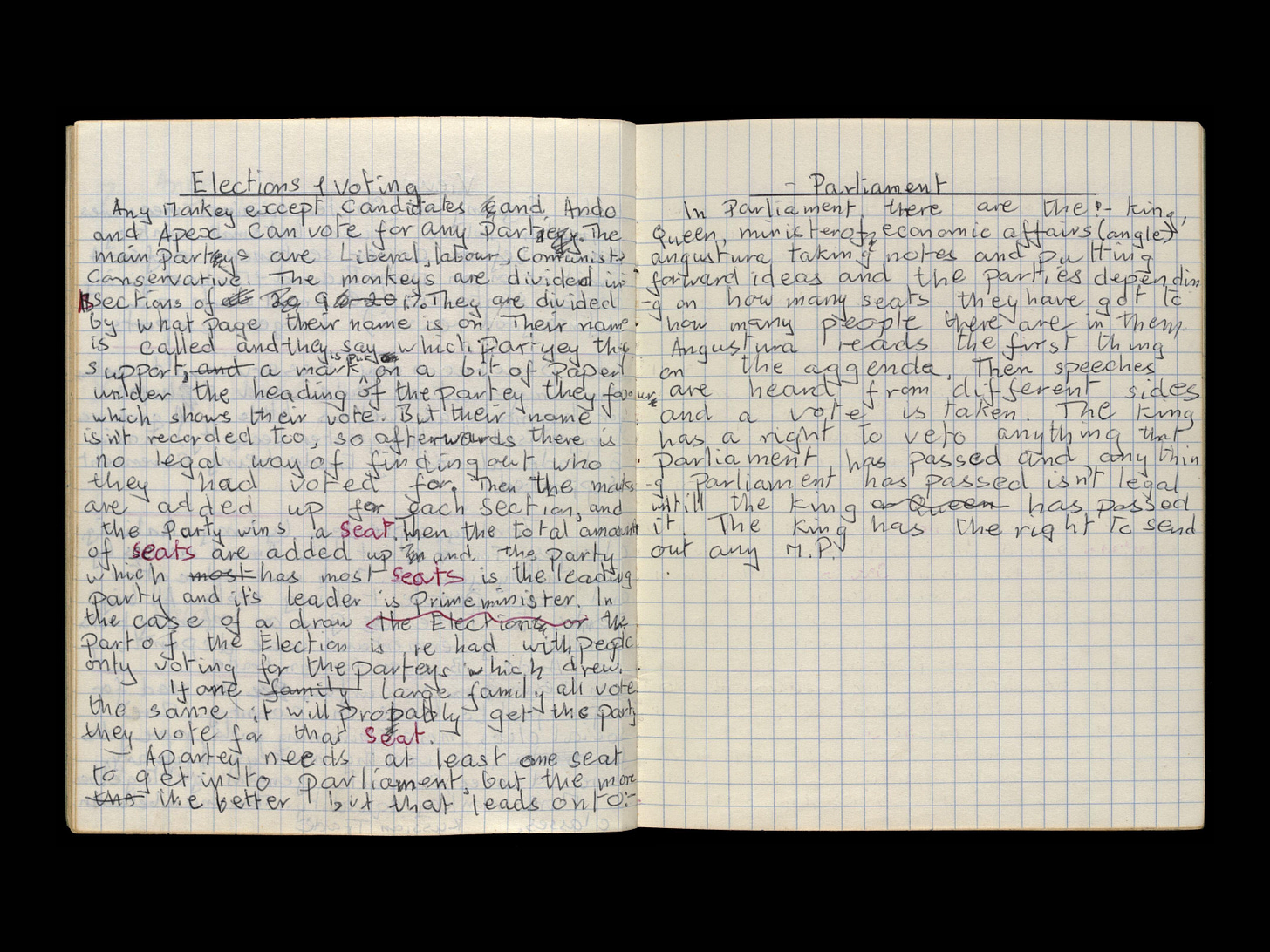

Exercise books captured the zeitgeist of their times and are now recognised as complex sources for studying the history of education. From discussions of the Industrial Revolution to essays on the Cold War, exercise books became time capsules, reflecting both personal growth and our historical context as humans. Even the V&A Museum holds a handful of them in their collection.

A best-selling author’s companion

Despite being home-schooled, Agatha Christie wrote all of her ideas down in standard school exercise books. She eventually became one of the world’s best-selling authors. What a legend.

Today — An object of desire

The exercise book was designed as a utilitarian tool for kids in classrooms. They still use them today, or at least they do in the UK. My partner, a high school teacher, has talked about “the death of handwriting” in the digital age, but I disagree. With screens dominating our lives, many of us are rediscovered the joy of putting pen to paper. As technology takes over, the need for a tactile experience grows.

High-quality stationery has transitioned from utilitarian tools into objects of desire; something to be cherished and experienced. Not just seen as bits of paper to scribble on, but a daily companion. A symbol that we’re still learning and growing. They invite us to slow down, think deeply and express ourselves, free from distracting notifications. Good ideas might start in your Notes app, but they’ll truly become great when you develop them on the blank page.

Until next time,

Callum